Sculptor Sheryl Jaffe and her husband Walter Buckingham are leaning over a table, sewing needles in hand, with the quiet concentration of surgeons about to stitch up a body.

The “body” on the table is a 6-foot length of thick, textured paper Jaffe has made largely from plants that proliferate nearby, and the two are slowly lacing together the folded spine of one long paper panel to the folded spine of another, and then another.

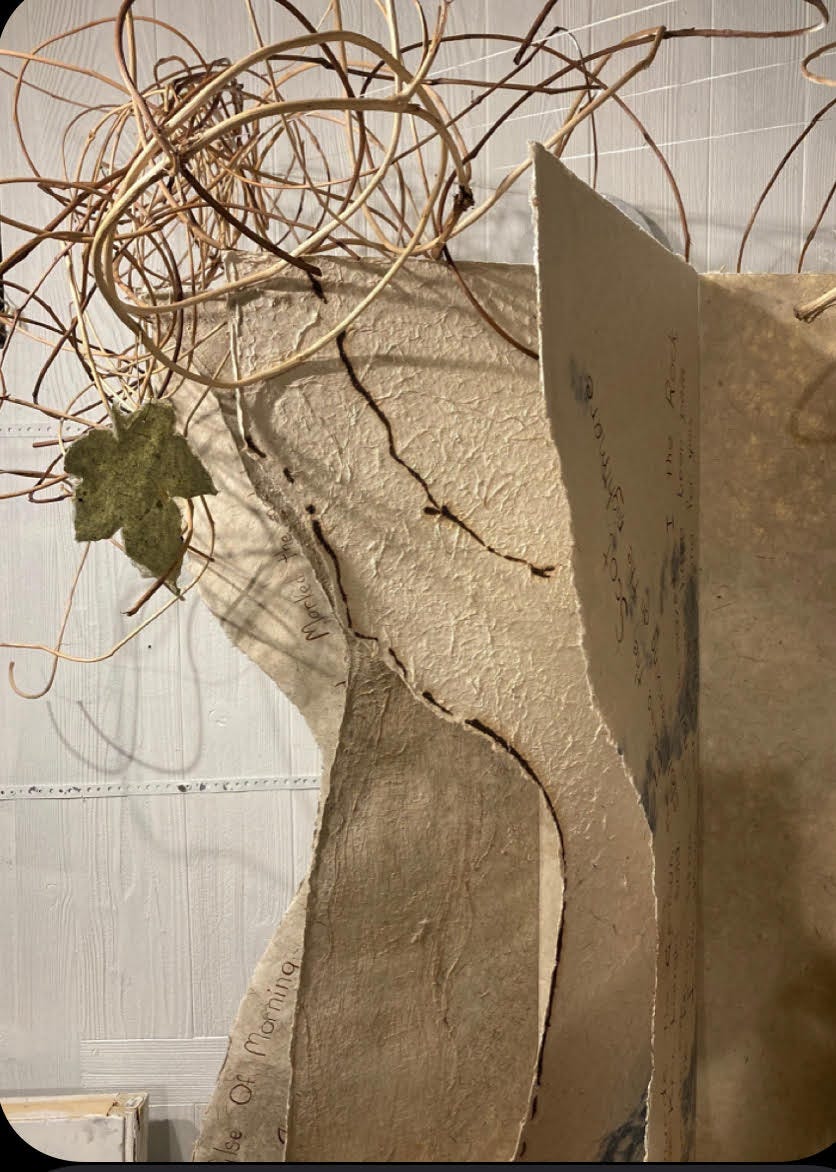

Jaffe and Buckingham are in the process of assembling Jaffe’s version of a book, in the form of a tree. When finished, the sculpture will stand upright on its own pages, the base flared open like a circular fan. Like an open book.

Its crown will be crafted from a rolling tangle of Wisteria vine soaked in a dye made from boiled down cedar bark and hung with hand-made paper leaves.

Running vertically down each panel like the currents of a river, or sap in spring, Jaffe has inscribed in cedar bark ink a poem by Maya Angelou called, “On the Pulse of Morning.”

It begins:

“A Rock, A River, A Tree

Hosts to species long since departed … ”

Why this poem?

“This is what Maya Angelou read at Clinton’s inauguration.” Jaffe says, “When you read this, you get that there’s no reason to read any other poem.”

Why written vertically on the body of the tree?

The idea, she explains, is to resemble the tissue lining the inside of living plants that carries water and nutrients up from the plant’s roots. It’s also meant to echo a belief of the Japanese Shinto religion that vertical things in nature transport the desires of earthbound beings to the deities in the higher-to-reach realms.

Jaffe had already taken a long, deep dive into pottery-making with its fundamental elements of clay, water, and fire, but it was as an art teacher teaching students black and white photography that, in an indirect way, led her to paper making.

“The photography paper just left me feeling far away from the process … it can seem almost plastic, not breathing but kind of dead and removed.” Her distaste for this sensory disconnect led her to ponder alternatives, which led to the idea of making her own paper to print on, which led to trying it as a new medium to explore in her three dimensional work.

Like pottery, Jaffe’s paper making technique is barely a few steps away from how it was first invented around 2000 years ago.

During China’s Han Dynasty a member of the court figured out how to boil down plant matter until softened (for her own paper Jaffe collects things like tree bark, Wisteria vines, grasses, Iris leaves, seaweed, banana stalks, flax, reeds, etc…) beat it into a fine pulp that then gets stirred into a shallow tray of water. When a flat sieve is lowered into the mix and then pulled up the water runs out of the fibrous substance back into the tray, leaving a thin skin of plant material clinging to the upper surface of the sieve. Then, by turning it over onto an absorbent surface, the film of pulp is released and allow to dry.

Flat, flexible, lightweight, and reproducible, plant-based paper went on to change the world. (More on the history of paper in a subsequent chapter of WonderLust)

I asked Jaffe what it is about making her own paper that captured her aesthetic interest.

“A big part is the process,” she says, “Finding a variety of plant material then cooking it in water to slowly break it down really transforms the raw materials into something else.”

She draws a parallel to working with potter’s clay, how it is softened and shaped by water, set out to dry, then exposed to a source of heat so extreme that its molecules are irrevocably transformed from clay to a soft stone.

For Jaffe it’s also the way making paper has elements outside of an artist’s control. The end result will always depend on how fine or coarse the raw materials themselves are beaten, how different fibers shrink, how its thinness or thickness affects the light coming through - aspects she can’t predict until she can pick up the finished sheet in her hands.

Having studied paper making in Japan, Jaffe’s well-versed in how traditional Japanese papers are made, and one can see in her pieces the balance between time-honored methods and the exceptional versatility inherent in the medium.

Her sculptures have the quality of movement in stillness. Some, lightweight and pale, seem to float, moon-like, gourd-like, others suspended, kite-like, in air. Many appear caught in the act of unraveling, or spinning like a dervish.

Often Jaffe will embed denser strands of contrasting fibers into the wet layers. She’ll draw figures on them, crumple them up then smooth them out. She’ll stitch pieces together like fabric, cut them in strips and weave one into another. She molds the stuff into organic shapes, and stretches white membranes of paper over bent branches or vines, like skin over bone.

Paper is clearly Jaffe’s playground.

When an artist like Sheryl Jaffe, who clearly has mastered her medium, remains not only intrigued by but cheerfully experimental with its ways, she is a creator worth keeping your eye on.

The tree/ book in process

******************************************

There are two upcoming exhibitions featuring Sheryl Jaffe’s artwork:

Her tree -shaped book will be included in the show:

“Book Arts: Conversation in Art and Words”

at the Cahoon Museum of American Art in Cotuit, MA

September 25th - December 22nd Opening reception October 5th

And a solo exhibit

“Made with Water”

At Wellfleet Preservation Hall, Wellfleet MA

October 4- October 29 —- Opening reception October 4, 4-6 pm

With an artist’s talk October 16th 6 pm

( Next post: A kind of apologia to WonderLust’s patient Lusters)

BRAVA SHERYL!-- so glad and so honored to be a camarada and a fan... and Thanks to Ellen and Walter for being right there on the team, cheering on & supporting Sheryl's beautiful, visionary nature-loving, poetry-loving work